If you see the teeth of a lion,

do not think he is smiling at you.

—Al-Mutanabbi

Where would you have gone? “Anywhere. I just wanted to go for the sake of going,”

Mahfouz Kabariti said. To fuel his escape he had bought a boat from an old Gazan

fisherman. On the day of the purchase, two years ago, as money exchanged hands,

people spoke in whispers at the port in Gaza. The word on the street was that

Mahfouz had gone mad trying to sail away from the only port on the

Mediterranean that lay dormant, in a boat with a rusted rudder, into waters patrolled

by the Israeli navy from a territory that was under siege.

“Perhaps hope had driven me mad,” he sighed, but he had no doubt that his rusty boat was the Titanic, rising above all the other traditional fishing boats docked at the port. He would call it Gaza’s Ark. This was, after all, the type of boat that could save the people of Gaza from the flood of Israeli disregard.

Two-and-a-half years later, after illegal purchases—of fibreglass, GPS navigation systems, wood and countless other bits and bobs that had been smuggled in from the tunnels into Egypt—after massive employment of architects, engineers, blacksmiths, aluminum welders, carpenters and plumbers, and after an expenditure of thousands of shekels of foreign-donated money, the boat was almost ready for its maiden voyage.

Cyprus or Turkey? That’s where he’d sail, carrying cargo from local Gazan businesses.

Not so fast.

In 1948, the population of Gaza was no more than 80,000. The Arab-Israeli war transformed Gaza. By the Six Day War in 1967, 1.8 lakh refugees were crammed into a sliver of land just over two per cent of Israeli territory.

While Mahfouz coordinated with a skipper, tensions in another part of Palestinian territory—the West Bank— rose and Israel, redressed by attacking the Gaza Strip, unleashing the wrath of collective punishment. On the third night of the attack, while Hamas fired rockets, and the thuds and booms of Israeli shelling and bombs terrified Mahmoud’s little daughter so much that she was too scared to use the toilet alone, the phone rang.

“Ya akhi (oh brother), the boat is no more,” said a fisherman.

Mahfouz could just about manage a whimper. Israeli naval warships had lobbed shells at the Gazan shore and as Gaza’s Ark went up in flames, it burnt Mahfouz’s dreams of breaking the blockade.

“I didn’t want to believe it,” he said. “Our project was 100 per cent peaceful. The Israeli always boast that their targets are accurate, how did we end up on their list of military targets?”

***

Gaza wasn’t always like this. In its heyday Gaza was a link

between East and West, a place where desert caravans journeying from Arabia

would offload goods only to be reloaded onto vessels cruising the

Mediterranean. Gaza’s market was a trading hub, a confluence of cultures and

languages. Agriculture in Gaza flourished as farmers earned prized reputations

as cultivators of oranges, lemons and grapefruit. Mahfouz recalls stories his

father used to tell him of Rafah, once a bustling market town that drew Egyptians

by the droves via the Palestinian railroad.

All changed after the Occupation.

In 1948, the population of Gaza was no more than 80,000. The Arab-Israeli war and the subsequent Egyptian occupation transformed rural Gaza into the dubiously named “Gaza Strip”. Refugees filtered in from other parts of Palestine as Jews began their Zionist project of creating a homeland. A demographic explosion took place as agriculture land made way for refugee dwellings, and fresh produce made way for UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) rations. By the time of the Six Day War in 1967, there were around 1.8 lakh refugees crammed into a sliver of land that is just a little over two per cent of Israeli territory.

By 1994, the strip was cordoned off by an electric fence, turning Gaza into a ghetto. When Israeli occupation formally ended in 2005, Gaza had been transformed into the world’s largest open-air prison.

The Gazans suffered another cruel blow in 2006 after voting Hamas into power in free and fair elections. Both the United States and Israel imposed a land, air and sea siege as punishment. Israel and the US label Hamas a terrorist organisation; Russia and China don’t. This blockade places severe restrictions upon people and goods in and out of Gaza.

In 2014, Egypt tightened the noose by closing its border crossing at Rafah and demolishing hundreds of smuggling tunnels that Gazans rely on for necessities such as food and fuel. On July 8, this trapped population’s situation worsened as Israel launched Operation Protective Edge, apparently because of a series of events that took place in the West Bank, the Palestinian territory that abuts the Dead Sea.

Darkness had already fallen over the West Bank when three

Israeli teenagers set out from their yeshiva (religious school) on foot

from the Gush Etzion settlement block. The Israeli settlement was nestled in

the hilly Biblical heartland between Jerusalem and Hebron, on the land where

prophets David and Abraham were said to have once walked, in Palestinian

territory. Red and white road signs dotted the tense landscape: “This Road

Leads To Palestinian Village The Entrance for Israeli Citizens Is Dangerous.”

Yet they hitchhiked.

An intense hunt for the boys followed. Hebron, Palestine’s largest city, was under clampdown. Trucks were stopped, houses searched and Hamas-affiliated professors, legislators and ministers arrested. Raids and blockades, deaths and shooting led Hebron’s mayor Daoud Zatari to accuse Israel of “collective punishment”.

On the eighteenth day, the intense search culminated when their bodies were found in a shallow grave, buried under a pile of rocks in an open field in the occupied West Bank.

This was the sort of place the West Bank had become: bitter, vulnerable, unsafe.

Where the wheat grew, Israel has established the Jewish settlement of Givat Zeev and in the fertile field, a prison. To the south of this area, near where I used to stand to watch the sunset, a highway has been built.

Observant and often fundamentalist Jews believe that when the Messiah comes, Jews exiled from the Holy Land by the Romans will return to Israel and peace will dawn upon earth. The religious Zionists take this belief further: rather than waiting for the Messiah, they believe they should expand and protect their land, thus ushering in the age of the Messiah. Northern West Bank is the heartland, and Orthodox Israelis often refer to it by its biblical name of Samaria.

Thus the West Bank has been transformed into a matrix of colonial settlements and checkpoints, Israeli-only roads and fences, walls and military bases. Raja Shehadeh—lawyer and author of Palestinian Walks, winner of the 2008 Orwell Prize—and I exchanged a series of emails after the outbreak of hostilities where he remembers a landscape that is fast vanishing.

When you open your window, what do you see?

From the window of my study where I’m sitting to write this, I can see my garden with its 350-year-old olive trees. They stand by the garden wall to the northeast. I made two flower beds around their ancient trunks, one higher than the other, to keep the soil from eroding. These are encircled by a short terrace wall built in the traditional way from interlocking stones carefully selected to stay securely in place without cement. Beyond the trees on the wall are various shrubs and climbing plants, pink Bignonia Contessa Sara, white jasmine and purple bougainvillea. What I have tried to do with this landscaping is to replicate the stone terracing in the hills surrounding my house which used to be terraced and cultivated with olive and fig trees with grape vines in between but have now been mainly taken over by the Jewish settlers. That’s the small piece of land left for me to enjoy.

The hills are changing: can you elaborate on this? How has this eroded the carefree abandonment of the countryside?

When I was a young man I used to drive in the summer months the short distance southwest of Ramallah to the adjoining village of Beitunia to buy tomatoes and cucumber from the fertile valley that, until the spring, would be submerged under water from the rain, making it the only temporary pool in the valley between the hills and enabling the vegetables to grow in the fertile silt without further watering, producing tomatoes that were especially astringent and delicious. It was also where I used to go to watch the sunset when I learned to drive. There the hills were soft and gently rolling.

In the summer, the whole area would look like a sea of brown wheat that with the wind made a faint swishing sound. I enjoyed leaving the car to sit on a stone and listening to this soft sound. In the horizon I could see the Mediterranean coastline and the real sea next to Jaffa, the coastal city where my parents used to live until they were forced out in April 1948, when the state of Israel was established. My world, and that of my parents, had shrunk by the loss of that area of Palestine on which Israel was established. This area near Ramallah to which my parents moved after they were evicted from Jaffa, that I used to enjoy visiting has now been transformed.

Where the wheat grew, Israel has established the Jewish settlement of Givat Zeev and in the fertile field, a prison has been built called Ofer Military Prison, which also houses the Israeli military court. Nearby a new checkpoint was established that prevents Palestinian traffic from crossing. To the south of this area, through what was left of the fields near where I used to stand to watch the sunset, where the wheat grew, a four- lane highway has been built connecting Jerusalem to Tel Aviv, providing an alternative road to the other link further south between the two cities. All along this new road Jewish settlements have been established.

Palestinians are not allowed to travel on this road. They have to use small circuitous single-lane roads to get to their villages along each side of this road. Sometimes they have to drive in tunnels built for them below the road, unseen by Israeli drivers. Many of those settlers using this road prefer not to remember that in the course of building this wide highway, thousands of acres of land had to be destroyed that belonged to the villagers who are now prevented from using it. These lands used to be terraced and cultivated mainly with olive trees, fig trees and seasonal vegetables. The old geography that I grew up with has changed perhaps forever, and a new geography that serves the interests of those who are illegally living in the occupied Palestinian territory has taken its place.

This sounds like a form of apartheid.

There are of course obvious differences between the two situations in terms of the history, the numbers, the nature of the societies involved. At the same time the description of the policy in Israel/Palestine as one of apartheid is apt.

As was the case under apartheid South Africa, Israel wanted to confine the Palestinians living in the West Bank spatially and in terms of their right to development, while allowing Israeli Jews living in the same territory access to more land and a disproportionate share of the natural resources and opportunities for economic development. This it did by marking out where the Palestinians are allowed to live and limiting their right to expand their cities and villages through restrictive zoning laws and schemes. In effect it created Bantustans where Palestinians are confined.

Israel also passed discriminatory legislation in the form of military orders that applied only to the Palestinian community not the Israeli Jews living in the same area. So living in the same territory are now two communities, Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs, each subject to different and discriminatory laws. This is classic apartheid.

Hindsight is 20-20 but if you were looking back, how would you read the current events?

The viciousness that is now in evidence is due to the short-sighted policies pursued by Israel which cannot imagine living in peace with its Palestinian neighbours sharing the land. Israel was ostensibly built to allow the European Jews to leave the ghettoes in which they lived and to lead normal lives. Instead Israel, by failing to make peace with its neighbours despite many offers over the years, seems to prefer to hold on to the land it occupied in 1967 and not to resolve the refugee problem that it created upon its establishment. It now claims that it is protected from the ineffective rockets fired at it from the Gaza Strip by the Iron Dome Defense System.

So from the European ghetto on to a new ghetto beneath an iron dome that provides the delusion of safety, and enables the perpetuation of the deceit that security is possible without negotiations and coming to terms with Israel’s neighbours and making peace with them.

Over the years, it has been Israel’s objective and expectation that by making life so difficult for the Palestinians living under an oppressive occupation, they will pack up and leave. All signs from economic strangulation to Jewish-only settlement building which now sit on the majority of land in the West Bank, point to this. Different laws exist for each group—laws that discriminate in terms of access to natural resources and freedoms and economic opportunity just as it was in apartheid South Africa.

The lesson that no people will accept to live under conditions of perpetual discrimination and indignity has not been learned by the right-wing Israeli government, which is still supported by the majority of countries around the world.

Can you envisage peace?

These times with the clampdown that has been taking place in the West Bank and the brutal bombardment from air land and sea of the Gaza Strip are reminiscent of the First Gulf War in 1990, when Iraq under Saddam was bombing Israel with what we thought might be missiles with chemical warheads. The Israelis were given gas masks. We were left to fend for ourselves. We all stayed in sealed rooms. It was false information that Saddam had the capability or intention of firing such rockets. After the war was over, I wrote my book (published in 1992) The Sealed Room. I ended that book with the following plea:

‘The Intifada means shaking off. I have been inside my sealed room long enough. The time has come to force open the doors of my mind and rejoin the world.

I want to leave my sealed room,

Will you leave yours?

Then we’ll meet halfway.

What do you say?’

Indeed that war was followed by the first ever negotiations between Israel and the PLO which led to the Oslo Accords that failed to bring peace. Would this new aggression lead to negotiations that with the necessary pressure from countries supporting Israel force it to withdraw from the Palestinian territories it has been occupied for the past 47 years? This would depend on whether the Israelis would realise that their only security comes from reaching peace with their neighbours, not from the Iron Dome that they seem to want to live under.

In Sderot, a group of Israelis brings plastic chairs to the hilltop, eating popcorn whilst watching the explosions in Gaza.

Peace remains elusive in the region. At the time of writing, 14 days have passed since Israel launched its attack on Gaza. Officials in Gaza claim at least 500 Palestinians have been killed and at least 13 Israel Defense Forces (IDF) soldiers have died. About 75 per cent of Palestinian casualties have been civilians and tens of thousands have been forced to flee. North Gaza is the scene of tense fighting as Israel attempts to destroy a labyrinth of underground tunnels that Hamas uses to launch attacks from.

***

He’s got 60 seconds to run after Hamas fires a rocket aimed

at Beersheba, a city in the southern Israeli desert. Whee-yooo. That’s the start of the siren. Ofer Cohen

says it sounds like the music that accompanies ghosts in Hollywood movies but

for him, it’s the soundtrack to an awful plot where he’s in a race against time

and Hamas—jolted out of sleep, scampering around the room in his boxers,

looking under his bed.

“Zohar. Here kitty, kitty, kitty. Zohar.”

She’s probably hiding under the table. No. Maybe next to the fridge. Maybe she’s curled up on the sofa. The small house suddenly seems big as the clock ticks and time runs out. He grabs the screeching cat; she scratches his arm, and they’re out into the corridor. That’s the safest place in the building. The bomb shelter’s too far.

Shalom.

His neighbour is outside in her grandma nightie, wailing while her husband struggles to lock the door. She fans herself with her hands, in the throes of hysteria. She glances at him, leaning against the wall topless with Zohar, the cat, under his arm.

They make small talk: how far do you think that fell, that was loud, rockets are getting closer. But as the night progresses and more rockets drop, no one is in the mood to be polite, let alone smell the others morning breath.

During our Skype conversation, Ofer Cohen’s mobile goes off: Red Paint. Red Paint. That’s the code word for a missile launched by Hamas heading towards Israeli territory. A free app sends that information.

All anybody talks about is the attack, the conflict. His world is frozen, his life on hold as streets are deserted, universities closed, bars empty despite the World Cup being shown. Nothing’s the same; even the news show he watches every night has gone berserk as presenter and panelists have relocated the studio in Tel Aviv to a rooftop that ensures them a vantage point.

Meanwhile in Sderot, a group of Israelis brings plastic chairs to the hilltop, eating popcorn whilst watching the explosions in Gaza.

The attacks used to be scarier. Hamas’s primitive rockets used to have greater success, taking more Israeli lives, but the Iron Dome changed all that. The Iron Dome intercepts 90 per cent of rockets that Hamas fires as radars track the incoming threat. The threat is related, data analysed and target coordinates are passed to missile firing units. Then the interceptor Tamir missiles are fired back at the source. The cost of one Tamir missile is approximately $60,000.

At the time of writing, over 1,500 have been fired and one Israeli has died because of Hamas rockets. Palestinian losses run into the hundreds.

Palestinians are sick and tired of this conflict and of the violence, but have little ability to do anything about it; they feel it has become a political game in which they are pawns.

But as Israel’s ground offensive takes more lives on both sides, he’s almost forgotten why it all began. The kidnapping, he says, was overplayed to stoke nationalist tendencies. These three teenagers were no Gilad Shalit, the Israeli solider that had been abducted by Hamas in 2006. Gilad’s five years in captivity had kept the nation captive simply because he was a soldier. Like Ofer Cohen was. Overnight he became everyone’s son, brother and husband. But the settlers, they were a different matter altogether.

“You can’t go into the lion’s nest and not expect to get bitten,” he says. Many liberal Palestinians clash with the settlers, he explains, calling the settlement issue the “worse crimes of this occupation”.

***

Once the bodies of the Israeli teenagers were found, another

went missing: that of Muhammad Abu Khdeir, a Palestinian teenager. According to

the postmortem findings, Khdeir had inhaled soot, implying he was still

breathing when Israeli extremists set him on fire in an act of revenge. The

gory details stroked tensions, and Hebron and East Jerusalem erupted.

Award-winning journalist Daoud Kuttab—the first Palestinian to interview Yitzhak Rabin, Shimon Peres and others with 20 years of experience—the Palestine correspondent with Al-Monitor, explains the current spate of violence.

The catalyst to the current crisis has been the kidnapping

and murder of three Israeli boys in Hebron. What are the dynamics like between

settlers and Palestinians?

Hebron is a city that is famous for its small industry and good business culture. The Palestinians of Hebron have an entrepreneurial spirit and work hard at making a good living although some would argue that they work harder at making money than on spending it. Hebronites have been plagued with the presence of a violent radical Jewish settlement population that has decided to live in the very centre of this bustling city and have as a result brought with them the Israeli army that protects them and thus makes the lives of Palestinians hell.

Settlers are known to harass the local population and make life difficult for their neighbours in an effort to force them to leave. The relationship has been that of the occupier and the occupied where the settlers and the army make up the occupying power. Even though the Israeli army pretends to be somewhat neutral, it isn’t. Even though many soldiers are secular and not very fond of the ultra-religious and rowdy settler population, which feels Hebron and all of Palestine is a God-given land exclusive to Jews.

East Jerusalem is now a flashpoint for conflict: Khdeir’s

body was found in the Jerusalem Forest. What is life like for boys his age, and

the anger Palestinians have towards the wall?

East Jerusalem is a unique city in that it was divided as a result of the end of the 1948 war that witnessed the establishment of Israel. In 1967, Israel occupied all of Palestine but put a lot of emphasis on capturing East Jerusalem and especially the old city, which has hugely powerful religious sites. For the Muslims, it hosts Al-Aqsa mosque which is the third holiest site in Islam; for Christians, there is the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Christianity’s most important location where Jesus was buried; and the Western Wall, important for Jews because of their belief that it is part of the old Temple.

I was hopeful when I interviewed Rabin, and felt he was genuine in his interest for peace, unlike the present prime minister.

Israel has put East Jerusalem’s Palestinians under civil law without giving them citizenship and this puts them in a different category from the rest of Palestinians in the West Bank. While East Jerusalem’s population has civilian laws, they are badly discriminated against. When the wall was established, it put a border between East Jerusalem and its natural relations with Ramallah and Bethlehem.

Israel’s attempts to isolate Palestinians from the rest of Palestine has failed politically even with the wall. Visit an Israeli neighbourhood and a Palestinian one in Jerusalem and you can witness this discrimination. This is the background to the lives of people like Muhammad Abu Khudair. No clear political horizon, difficulty to integrate with Israel, and barriers to integrate with fellow Palestinians.

This sounds similar to a form of apartheid.

Israel has a problem in the West Bank and Gaza; they are refusing to give it up to become an independent state. At the same time are not annexing it to Israel, while they are allowing Jewish settlers to move in, against international law that forbids an occupying power from transferring its people to occupied areas. This is creating a situation where Israelis Jewish settlers have freedom of movement, can vote in the Knesset, and get subsidies on water and other essentials, while Palestinians suffer. As a result an apartheid situation is taking place in the occupied areas, similar to that in South Africa.

Working as a reporter for so many years, what changes have you noted?

I was hopeful when I interviewed Rabin, and felt he was genuine in his interest for peace, unlike the present prime minister who is looking for ways to avoid peace. Palestinians are sick and tired of this conflict and of the violence, but have little ability to do anything about it; they feel it has become a political game in which they are pawns being moved from one party to the other without any feeling about our lives and future. Violence has grown much more and has become much more intense, and violating people’s lives has made life so cheap that people die in large numbers without anyone caring.

Is the current violence because of Hamas’s rockets or is it political?

Israeli accusations against Hamas clearly were a precursor to the current war on Gaza, which aims at weakening Hamas (although it has politically strengthened them) and to destroy the unity between Hamas and PLO.

***

Operation Rainbow, 2004. Operation Autumn Cloud, 2006.

Operation Hot Winter, 2008. Operation Cast Lead, 2009. Operation Pillar of

Defense, 2012. Operation Protective Edge, 2014. Israelis claim these are military operations to ensure the

security of the state, that they are

acts of self-defence, but he just calls it genocide.

Accustomed to Israeli brutality but by no means immune to the fear, Gazans fell into the familiar mode of anticipating the worst. Israeli anchors said an attack loomed, Netanyahu barked on TV and the war drums were dug out but he couldn’t hear their beat.

This was the hour of preparation. Certain things were a given: there would be no power as Israel which controls power supply would cut lines, a water shortage would follow, and food would dwindle.

Ramadhan Kareem. Happy Ramzan.

Mahmoud Alarawi went out to the market and purchased a lead battery; this would mean they would have power and crucially, they would have Internet. Facebook and Twitter, he said, would be the most reliable sources of information because nobody trusted the news anymore. His father popped out to the market and stocked up on bread and vegetables and his mother took a trip to the pharmacy. In all corners of Gaza, people young and old, spoke of the imminent attack and waited.

His father, a veteran of Israeli aggression, paced around the house, getting all their papers together—identity cards, birth certifications, registration papers, certificates and passports—and packed one suitcase and left it near the door.

Sixty seconds. There was no siren but the Israelis were courteous: they would call and ask the family to vacate or would throw a non-explosive bomb that would make a shrill noise, an indicator that the house they were sitting in would soon be bombed.

Evening turned into night and nothing happened, so Mahmoud let his guard down. Maybe a change of heart, he thought, maybe tomorrow, and ventured out to the beach where people smoked shisha and played cards after a day of fasting and prayer. No sooner than he’d been dealt a good hand, the first explosion took place.

Boom.

Then there was fire. Smoke.

The calm was replaced by chaos. People ran frantically in all directions to a chorus of ringing mobile phones. Many ran towards the fire to help the unfortunate who may have been trapped or injured, but Mahmoud got in a taxi and made his way home.

In the morning, once the bombing stopped, the Israeli newsreader read out the numbers. Scores had died in Gaza, none in Israel. Then she read out another series of scores: the World Cup match results.

If the apocalyptic sight wasn’t enough, the taxi broke down one kilometre from his house and so he walked home in what looked like a scene from a Tom Cruise end-of-the-world movie. He was beyond terrified; he’d been away from Gaza for some time, in another world studying in the calm of Italy in the comfort of a fine arts institute.

The night was “hot”. His nephew, just shy of one year, cried as bombs rained in. The family—two sisters, two brothers, a sister-in-law, his parents—tried to calm him down: with each explosion they’d burst into laughter and soon enough the little toddler was amused. Together they laughed as Israel wrecked homes and lives in Gaza.

But this was no laughing matter. There was no shelter, no bunker, so the family crammed into a room with no windows but that meant nothing: if a bomb hit, they were all dead.

“It’s crazy. I will spend my life earning money to buy a house and then it may get bombed,” he says.

Nobody slept that night. In the morning, once the bombing stopped, the Israeli newsreader read out the numbers. Scores had died in Gaza, none in Israel. Then she read out another series of scores: the World Cup match results.

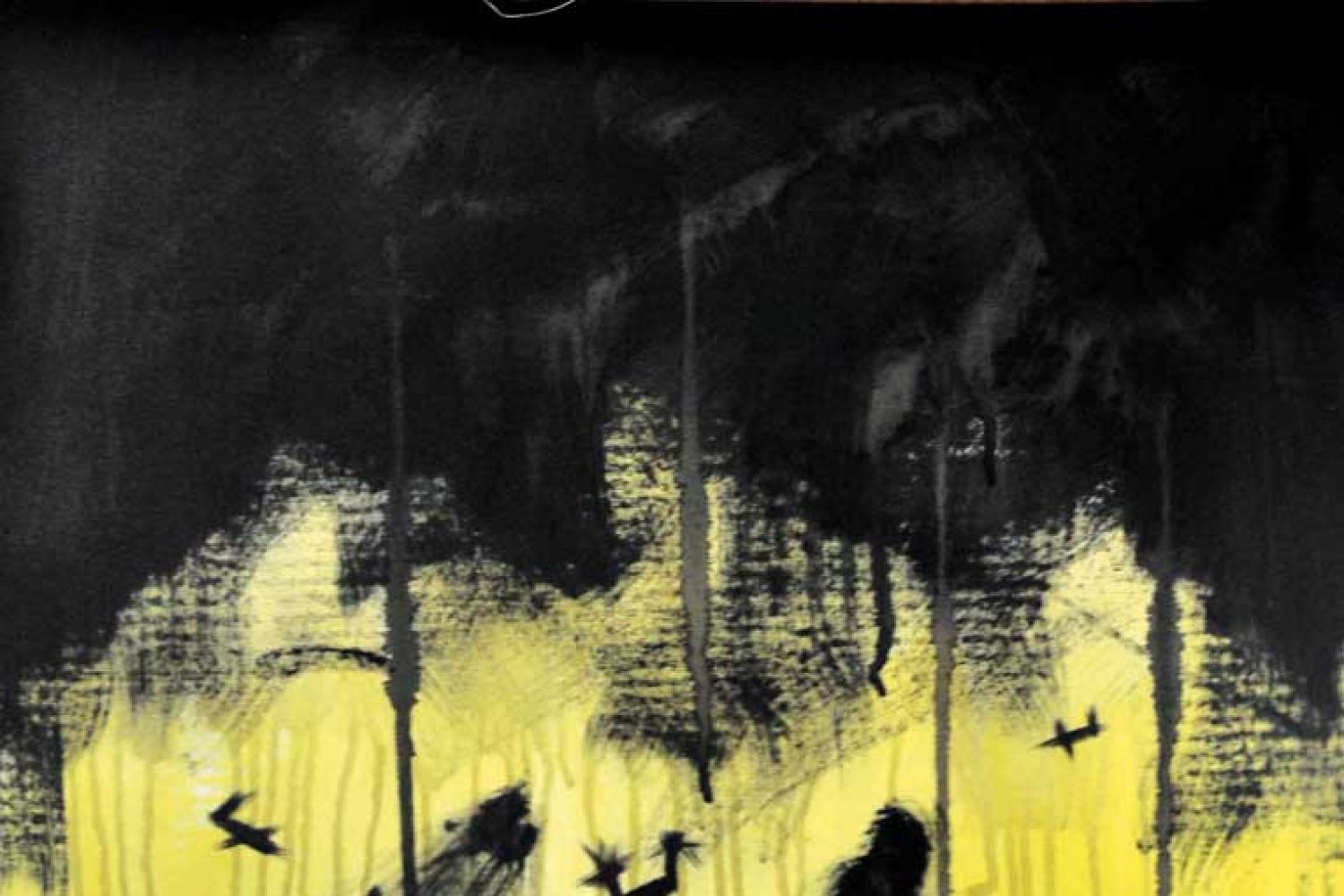

Mahmoud dreamt of being an artist and Palestine was his muse. Listening to the anchor, he was struck by an idea: War Cup. In the 3D image, there is a stadium with no audience, no referee, just tanks, jets and naval boats against houses above which rises the Palestinian flag.

“The news lied. They weren’t targeting fighters but houses, and so it’s a match between an army and houses,” he said over the phone from Gaza.

***

Israeli historian, social activist and author (Gaza in Crisis: Reflections on Israel’s War against the Palestinians, published alongside Noam Chomsky), Ilan Pappe is a professor at the College of Social Sciences and International Studies at the University of Exeter in the UK. He puts the crisis in context.

What are we seeing? Genocide? Apartheid?

Apartheid, for sure. The legal infrastructure, the physical segregation on roads, schools, areas of habitation, and the discrimination in all walks of life which is purely based on ethnicity and nationality leaves very few doubts about the validity of the term.

Listening to the anchor, he was struck by an idea: War Cup. In the 3D image, there is a stadium with no audience, no referee, just tanks, jets and naval boats against houses above which rises the Palestinian flag.

Genocide is incrementally happening in the Gaza Strip as the Israelis have no idea how to handle it. They hoped ghettoising would domicile the Palestinians but whenever they have had enough and rebel and resist, Israeli actions turn into genocidal policies because of the particular geopolitical location of the Strip locked between Israel and Egypt.

To what extent has support from the US permitted Israeli aggression?

Ever since 1967, the United States has immunised Israel against any international condemnation against its policies vis-à-vis the Palestinians, and American financial and military support is crucial for Israel’s ability to maintain the occupation for that long.

What can the international community do?

It is highly important for the international community to exert pressure on Israel to stop its oppressive policies; in the same way it forced apartheid South Africa to abolish the discriminatory regime. There, BDS—Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions—is a crucial campaign for justice and peace in Palestine.

Hamas and Fatah unity: could this have been a precursor to the current attack?

The unity government was indeed a trigger as far as the Israelis were concerned. After all, it challenged the divide-and-rule policies that enabled Israel to deepen its colonisation in the West Bank and the ghettoisation of Gaza as the best means to control the whole of historical Palestine without granting full citizenship to the Palestinians, who are nearly half of the population between the River Jordan and the Mediterranean.

What impact will the Iron Dome have on future policy?

The Iron Dome allowed Israel mainly time to consider how best to respond to the Hamas struggle. It prolongs the time it can take before it feels obliged to initiate military action, such as land invasion, the army is reluctant to take and continue for a longer period with indiscriminate bombing from the air.

***

The ticker on www.israelhasbeenrocketfreefor.com

ticked at the time of writing. Three hours, 52 minutes and 4 seconds, and then

it reset. That’s how long militants from the Gaza strip waited before they

aimed the next rocket at Israel.

The Qassam rockets were improvised devices, made in garages and basements from items you could find at DIY stores: pipes of steel, cast iron and aluminium, but these objects of possible destruction were on the list of prohibited items mandated by the Israeli authories. Fuel too was difficult to come by so militants improvised: melted sugar and fertiliser fuelled the rockets.

Hamas and other militant groups—Palestinian Islamic Jihad (Quds rockets), the al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades (al-Aqsa rockets), and the Popular Resistance Committees (Nasser rockets) —had come a long way. In 2001, when Hamas first launched its rocket, it barely cleared the border but in 2012, the rockets reached as far as Jerusalem. In 2014, it travelled 93 miles into Haida.

The warheads, usually made of homemade explosives, weren’t any kind of “game-changing Doomsday weapon”, Yaakov Amidror, the former national security adviser to Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu, said to the The Times of Israel. Instead, their intended effect was to create hysteria and fear as the Hamas-affiliated Qassam Brigades spokesman tweeted: “Rockets’ mission is to say: no calm & no security for the occupiers at the expense of our people. #Gazaunderattack”.

A small but notable presence of M302 Syrian-made rockets has been discovered by IDF during this skirmish (though the IDF says there aren’t many of them) yet the operation has intensified with the aim of wiping out the Hamas arsenal.

To destroy all the rockets and the immense network of tunnels used by Hamas to hide and move the weapons, Israel would have to go much further into the Gaza Strip, this when hundreds have already died and 80,000 Gazans have sough sanctuary in 55 UNRWA shelters, tripling in the past three days reflecting the intensity of the conflict.

***

“Where are you?” he asked. In Bombay. “Imagine every 12 hours there’s a siren in Bombay. Imagine

you have to stop everything you are doing, taking a shower, writing a story,

putting your child to sleep, and you have run to the nearest shelter. When it’s

over you have to go back to life. Can you pick up where you left off? No. I

don’t think so. What would you do? I don’t think the Indian government would

accept rocket attacks,” he says over the phone from Tel Aviv.

“But it’s not that simple.”

“No. It’s not. But this is fact. We are being attacked. Why should we tolerate the rockets? It’s not fair that the Palestinians are seeing the lands of their fathers being changed but we are being shot at. But why should we not use our F16s?” he asks.

“It’s an eye for an eyelash though.”

“Just imagine somebody doing this to Putin. He’d level the whole area this was happening in. Or Syria. We’re seeing what’s happening there. Whole cities have vanished,” he says.

He’s a former pilot from the IDF.

***

Two parties—Hamas and Fatah—both alike in popularity, in

Al-Shati refugee camp in Gaza, where we lay our scene, break from a seven-year

grudge to form unity, where a new alliance builds bridges between old enemies.

It is April 23, 2014, and Hamas and Fatah have signed a new unity deal despite condemnation from Binyamin Netanyahu.

“Whoever chooses Hamas does not want peace,” he says in a statement, and the US wags its finger. But the bitter divide between Gaza’s Hamas and West Bank’s Fatah that began in 2007, led to a brief yet bloody war closed as the two parties formed a unity government in Palestine on June 2. The two foes were united. Some felt these agreements were nothing novel, similar ones that been signed in Cairo and Doha but meant nothing.

They are saying Abu Mazen (Abbas) was offered peace but he selected war. This is odd. When we were united, they did not want to negotiate, but now when we can be divided, they are willing.

There are ideological differences, the thorns in the rosy picture. Hamas is interested in an Islamist agenda while Fatah rejects it. Hamas opposed a two-state solution while Fatah supports it. Hamas has no intention of losing control over its territory in Gaza and Fatah shows no interest in sharing the West Bank. Despite this, tensions on the ground may have led to this political compromise.

The economic meltdown in Gaza threatens Hamas’s popularity. Despite the Israeli siege, the smuggling tunnels running from Egypt to Gaza provided Gazans with a much-needed lifeline, but after General Sisi’s coup that overthrew the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Gaza suffered. Hamas is an offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood and the paranoid general closed the Rafah border and demolished several tunnels. The result was extreme fuel shortages, a halt in construction, water shortages, and abysmal sewage conditions. Now, Hamas needed Fatah.

On the Fatah side, analysts saw the agreement with Hamas as a last ditch effort by President Mahmoud Abbas of the Palestinian Authority to exert pressure on Israel (a sworn foe of Hamas) to make concessions on the settlement issue as peace talks brokered by Kerry looked doomed.

Both Hamas and Fatah, however, view Israeli disapproval as unjust: this unity, they maintain, is an internal matter. Neither Hamas nor Fatah shied away from talks with Israel despite the presence of an extreme right-wing government.

***

Ambassador Riyad Mansour, the Palestinian representative at

the UN, answered questions from New York regarding the unity deal, and how the

international community should respond to Israeli attacks.

To what extent is the current crisis a response to the Hamas-Fatah unity deal?

The Israeli government declared their opposition to the national consensus and they asked all other countries to oppose this government. They were demanding the fragmentation of the government, determined to go back to the status quo where there remained division of the two parts of the state of Palestine. But they didn’t succeed.

Israel decided from day one that Hamas had kidnapped the three settlers but have not presented evidence to that allegation. Hamas continues to deny it. Yet they embarked on collective punishment for the entire West Bank.

In fact they failed in convincing anyone, including the US, because international powers considered this government that of Mahmoud Abbas and he agreed to honour the Hamas-Fatah unity deal. The political objective is to try and show that this national consensus government including Abbas and Gaza is helpless, that they can’t take care of their needs, and that the government needs to be dissolved.

What they are saying now is that Abu Mazen (Abbas) was offered peace but he selected war. This is odd. When we were united, they did not want to negotiate, but now when we can be divided, they are willing.

After the Israeli bodies were found, some people put up the blue tents that are a precursor to a new settlement. Is there an end in sight to this illegal construction?

The radical solution to this situation, to the tragedy of the Palestinian people, is that occupation needs to end. We need to move towards a two-state solution that can be a reality on the ground. The Israeli state is unwilling to come to terms with this reality. Even in the recent round of negotiations with (US secretary of state) Kerry, the Israelis did not come to the table in good faith.

The original Zionists were mostly practical men and women looking for a refuge from the horrors of European oppression and had little time for the millennial transcendence of the new wave from Warsaw Pact Europe.

That they allow for the construction of settlements speaks louder than anything they say. This says they have no desire to evacuate our land, but should they not be involved in preparing their people for an evacuation? Yet the signal to the Israeli public is that they are looking to build more settlements. Why? This part is not going to reach any conclusion.

Israel will respond if rockets are lobbed on its territory. Can you envisage an end to Hamas rocket fire?

Israel decided from day one that Hamas had kidnapped the three settlers but they have as yet not presented evidence to that allegation. Hamas continues to deny it. Yet they embarked on collective punishment for the entire population of Hebron, then the West Bank. Israel is an occupying power; it has to, by international law, supply protection for the civilians under its control. Israel is not just failing to provide protection but it is forfeiting its responsibility to do so under international law. What’s more is that the concept of self-defence is when states fight each other. Of course Israel should protect its own people, but to attack the population you should protect is illegal.

But Israel views Hamas as a terrorist organisation.

Even the PLO is labelled a terrorist organisation, yet Mahmoud Abbas visits the White House to meet with President Barack Obama. Many Israeli leaders were labelled heads of terrorist organisations by the British mandatory powers—some were even sent to jail—but they were sought as leaders by the people of Israel. Killing civilians should be condemned and those involved should face justice but for political groups struggling to end occupation, one needs to distinguish between terrorist and national liberation movements. PLO and Hamas are struggling for freedom and for the national rights of the people but those who carry out activities not congruent with international law should be acted on.

The blockade, the siege, the settlements are all against international law yet the UN fails to act. Why?

The UN is failing to act because of political pressure and is not acting in a way that is congruent with the provisions of international law. What is the UN—it is what the member states want it to be but member states use double standards. Sometimes they uphold the law and at other times they trample on the law. They use the law for certain objectives and ignore it for others. This is for political reasons. This is double standards and we are victims of it.

What should countries such as India do in order to uphold international law in the Palestine question?

Countries need to uphold international law and ensure it is respected. Occupation, settlement activities, are illegal in US and Indian textbooks. If you say it is illegal and Israel ignores this, then just stating illegality is meaningless if it is not followed by consequences. So countries need to stop dealing with those who engage in settlement activities, not to allow this illegal enterprise to carry on, not to buy products from the country that breaches this law. This needs to be placed upon goods, financial institutions too. Those extreme settlers, like the ones who kidnapped Mohammed Abu Khdeir, need to be labelled terrorist organisations and visas should be denied them and they shouldn’t be permitted to travel. They should be detained to face the justice system.

***

When the current war was on its fourth day, an Israeli friend went to a protest in Tel Aviv where a group of people were staging an anti-war protest. Soon they were under attack by skinheads who wore T-shirts with neo-Nazi slogans. That never made it to mainstream news.

Similarly, Channel Two, Israel’s highest-rating TV news network, ran a story that alleged that UNRWA was transporting militants in Gaza in its ambulance. Channel Two later retracted this story.

The original Zionist settlers were mostly practical men and women looking for a secure refuge from the horrors of European oppression, which culminated in the Holocaust. They were a varied group—including socialists, communists and virtual atheists who had little time for the millennial transcendence of the new wave from mainly Warsaw Pact Europe.

On the other side, for the Palestinians of Yasser Arafat’s generation, it was about territory and homes lost to what they saw as an unjust and illegal occupation, not Islam or religion.

Even in the worst days, there was always a chance that sense could prevail. It nearly did with the Oslo Accords of 1995, anchored by the practical old guard of Yitzhak Rabin and Arafat. But all that has changed now with the advent of the zealots. The studied moderation of a Mahmoud Abbas has no chance against the hard religiosity of Gaza’s Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh or Israel’s Netyanahu.

Indeed the issue itself has been lost to ideology, a situation where myths masquerade as fact. Perhaps the reason Arafat wore his keffiyeh (black-and-white head dress) peaking at the top, draping low on his left shoulder that tapered at the bottom, was because he liked the look. Maybe it resembled the map of Palestine because we were looking for signs of the conflict in the most unlikely places, an almost monomaniacal search for symbols everywhere.

Too many stories are hidden, too many tall tales are spun, while the interested parties never really invest in peace talks. Meanwhile, the UN passes resolution after futile resolution though everyone knows it’s locked in permanent standoff on this.