It’s 8 o’clock on a

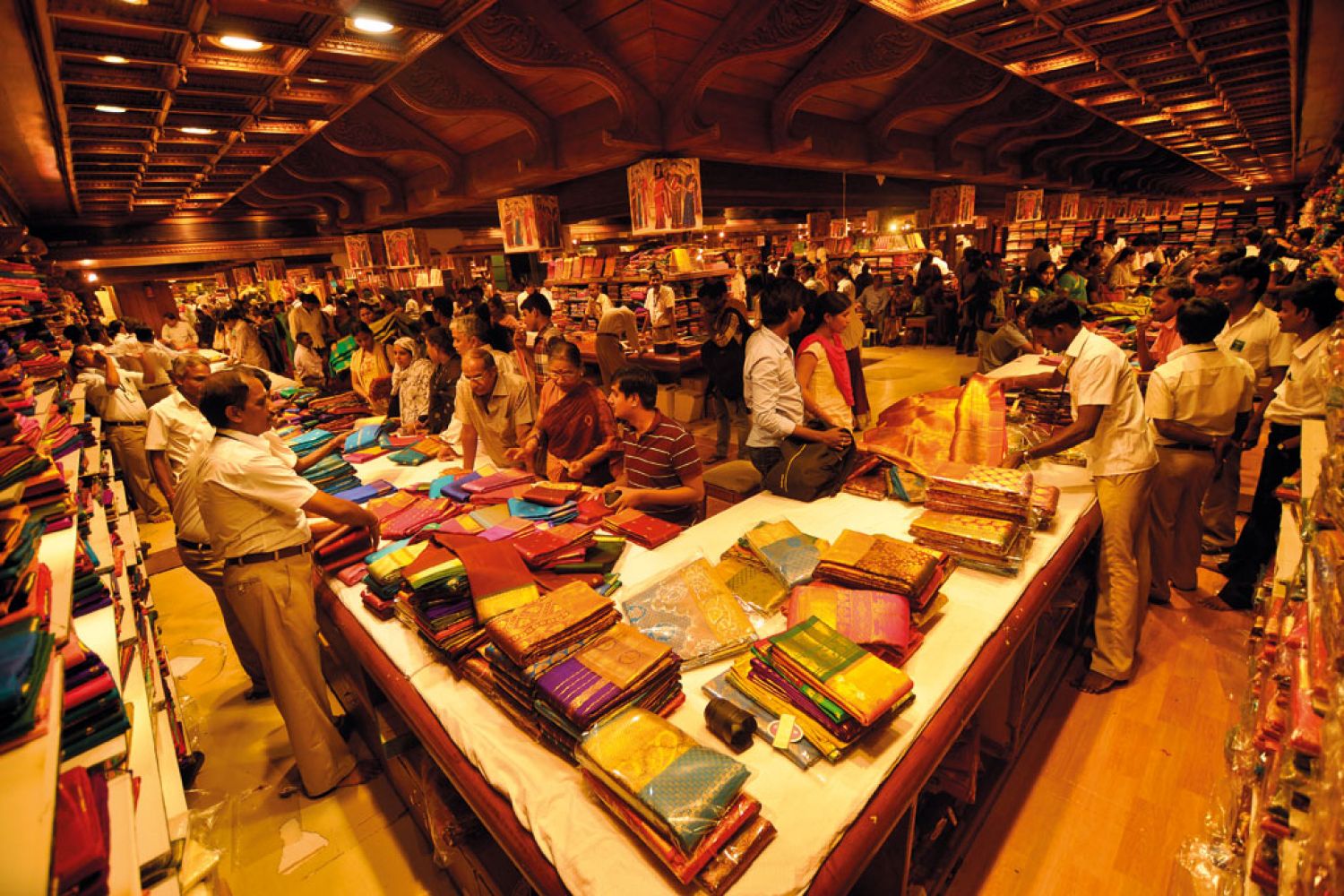

Tuesday morning. Most of the shops on the stretch of Pondy Bazaar in Chennai

still have their shutters lowered, while the pavements see fractions of people

slowly setting up shop for the long day ahead.

Nestled in the tight

space between Milan Jyoti clothes store and an ice cream outlet (“Rain or

shine, our softy is fine”), a man is vigorously scrubbing clean a stout black

Ganesha that sleeps in the alcove.

Water sloshes out of

his orange bucket as he move