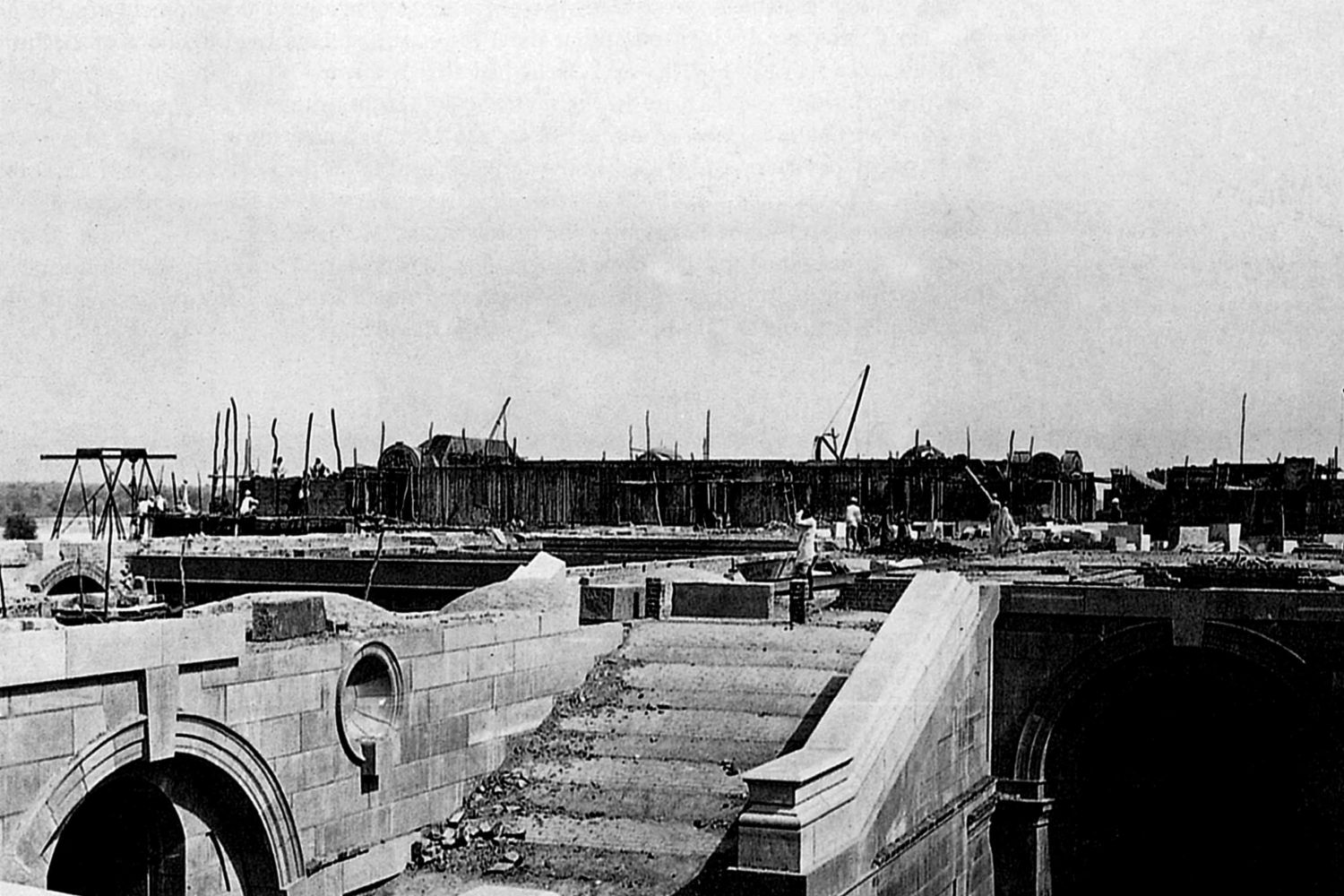

On December 12 last

year Delhi celebrated 100 years of the announcement by King George V that the

capital of India would be moved from Calcutta to Delhi, a year after the

Viceroy proposed doing so, for obvious geopolitical reasons. The announcement

was made by the British without any previous notification, during the

Coronation Durbar in a grand ceremony fusing the British and Mughal traditions

where they were proclaimed the Emperor and Empress of India, to commemorate

their coronation in

Continue reading “The natives strike back at the Raj”

Read this story with a subscription.