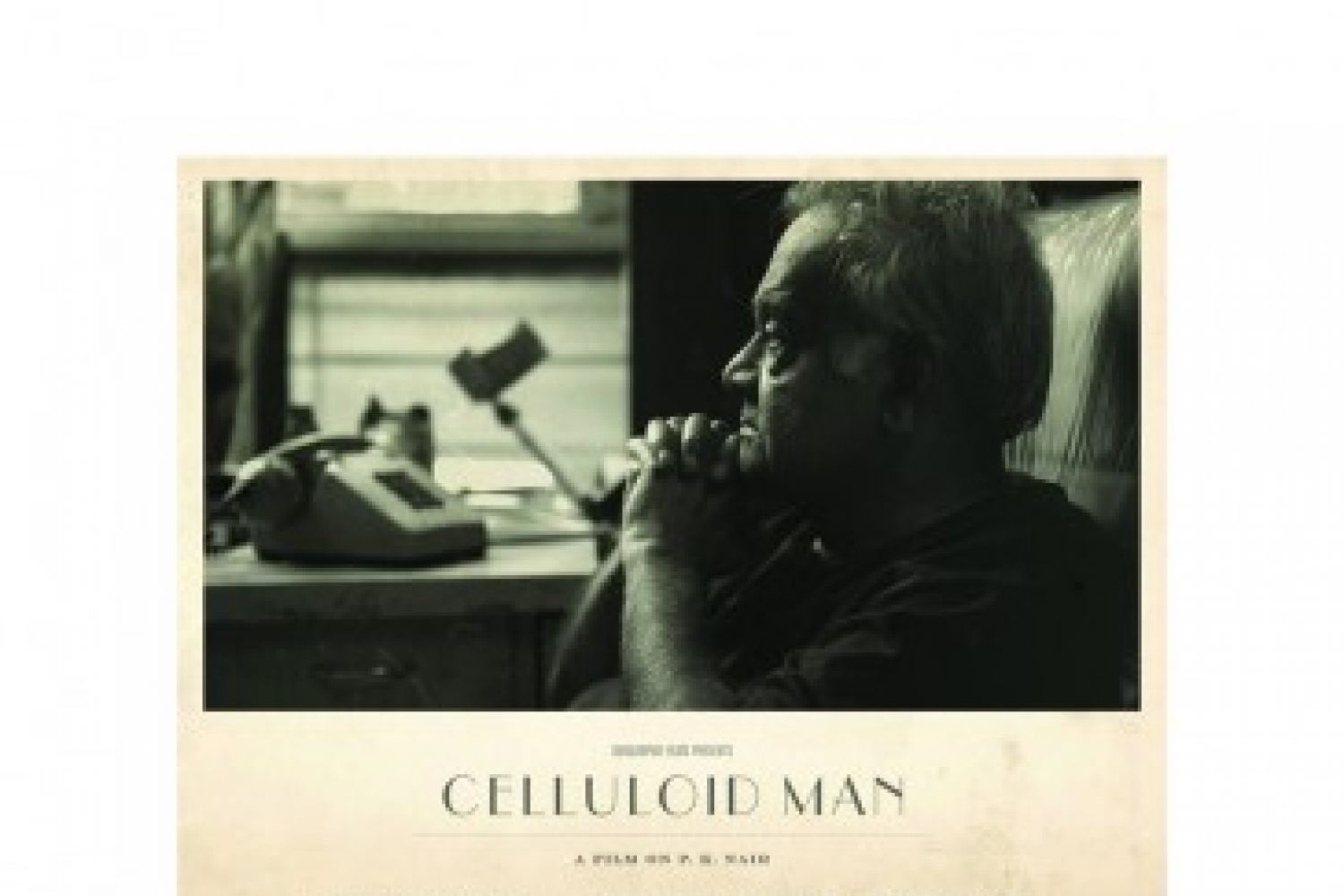

K P. Nair is the pioneer

in the preservation of films in India. He ran the National Film Archive of

India (NFAI) in Pune practically single-handedly since its inception in 1964

until his retirement in 1991. The NFAI contributed immensely towards exposing

would be film-makers enrolled at the Film and Television Institute of India

(FTII) next door to the riches of world cinema and, indeed, whole new cultures

that would have been beyond their ken.

Over the years famous

and not so famo