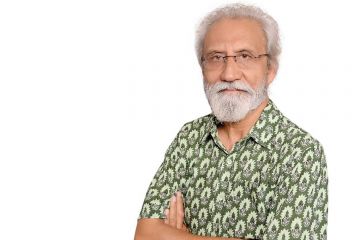

Sara Joseph is among the greatest Malayalam writers and known for deeply evocative novels and short stories at once deeply rooted in the local and universal in their scope. A pioneer of the feminist movement in Kerala, she has also been at the forefront of various ecological movements in the state.Sara Joseph is the founder of Manushi (organisation of thinking women), a movement that has had a significant impact in mobilising women from various strata of the society. She joined the Aam Aadmi Part

Continue reading “‘Activism gives you the eye of reality’”

Read this story with a subscription.