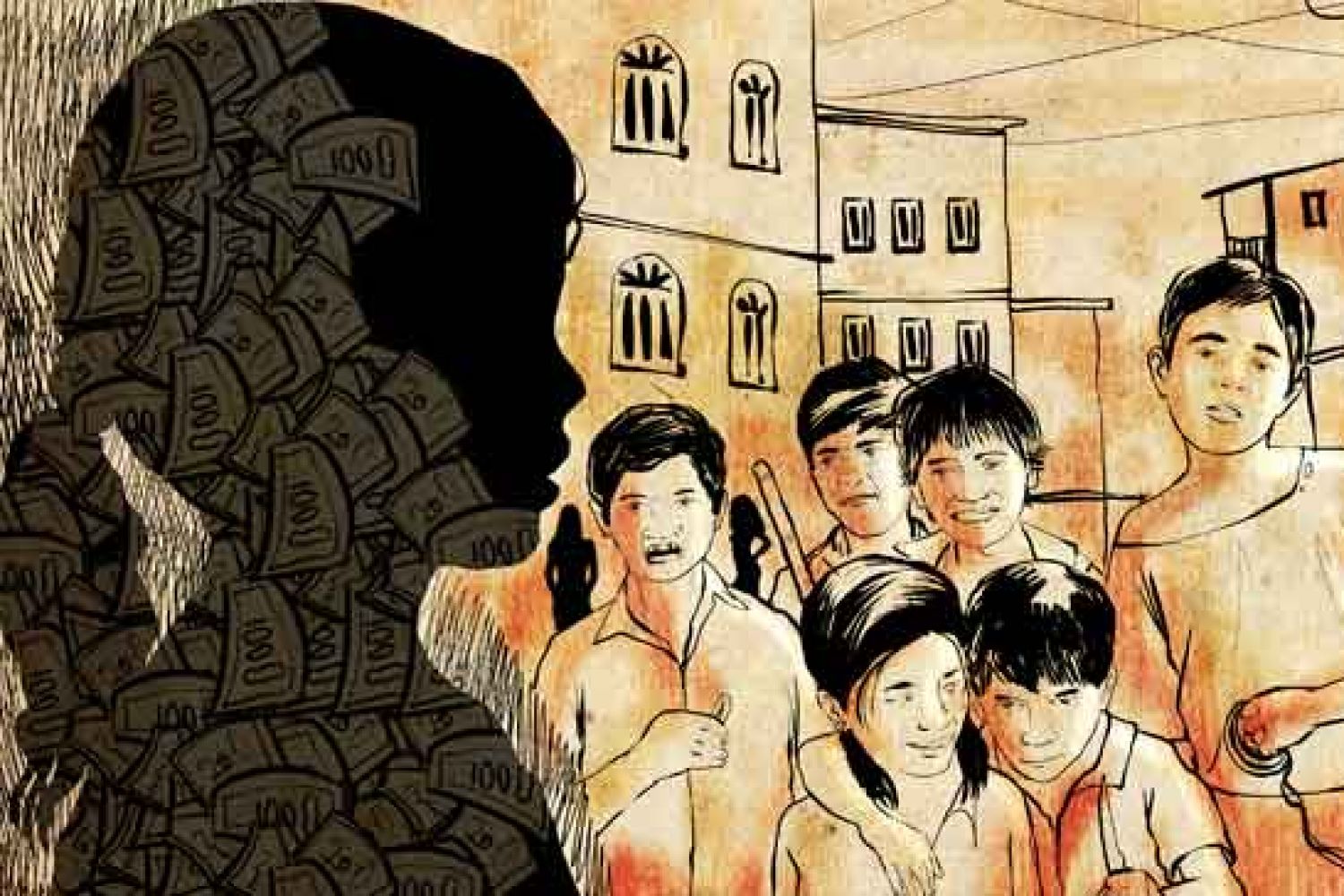

Sonali stares proudly at the three hundred-rupee notes, a couple

of fifty rupee-notes and an assortment of smaller notes bunched up in

a smelly handerkerchief, in addition to a wristwatch and umbrella.

The watch and umbrella together will fetch another two hundred rupees

or so. She has managed a full pack of cigarettes, another with three

or four, a lighter and half a bottle of rum.

Quickly, she hides one of the hundred rupee notes and the loose

cigarettes—just seconds before her brother