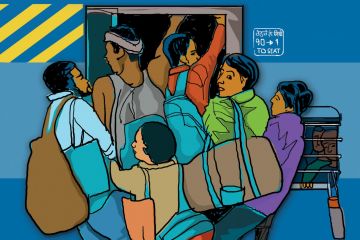

The great Mumbai

public throngs the streets of Lokmanya Tilak Marg on a balmy Monday in December

2011. A woman in a pink sari saunters by, speaking on her mobile. A man in

brown shorts manhandles a large red container along the street and another

selling striped T-shirts on the pavement calls out to passing customers. Except

for a speeding motorbike, a man carrying a large basket of papayas on his head,

and a man in a green and white shirt pacing back and forth, nervously looking

left and