Shilabati, 9, is named after the river flowing by her village

Chachanpur, in West Bengal’s Bankura district. The village has long had a

school, the present one being a

four-room all-weather structure. But it still has only one teacher. The state

government couldn’t recruit a single teacher in the last seven years. So, one

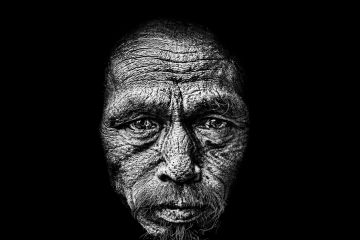

elderly man plays hide-and-seek with his 80-odd students at Chachanpur Primary

School. If he is sick, or goes on an errand, Shilabati and her schoolmates go

to the